Martha's Brighton.

The Brighton Bun

There really was one and its history is a bit strange. First let’s dispose of the interlopers. There is a Brighton rock bun or cake. This was made in the 1840’s but uses the newly invented baking powder. It even turns up in Mrs Beeton. What we are looking for is the real Brighton bun, something that Martha could have eaten.

The late 18th century was the beginning of the bun as we know it today. The Bath bun, Chelsea bun and the Sally lunn were all invented around this time as we think was the Brighton bun.. We can guess how they would have looked and been made but we do not know what flavourings or fruit would have gone into the Brighton bun that would have made it different from the others.

The Brighton bun like the others would have been made using yeast as a raising agent, flour, eggs would have been included, and the result would have been a bit like a brioche. Sugar could have been added but not necessarily as sweetness could have come from the addition of dried fruit and spices. I don’t think it would have been savoury, but it could have included carraway seeds either in the mix or sprinkled on top of the finished bun after it had been given alight sugar glaze.

So how to find the recipe? I started to search online and came across an old face book thread. The Brighton Bun had been made in Cannock and Walsall, between Wolverhampton and Birmingham. People had it as kids after school and had loved it. Yet it gets stranger. The buns were baked by Taylors [now no longer trading] and though this is a common name is also an old Brighton family name There were pictures online of a large, iced bun. The original would have had only a light sugar glaze as icing sugar back then was made by hand and could take hours to produce.

So, I am still looking for a recipe when I have one or invent one I and my friend Ian, who is the baker, will try out different flavourings and let you know. In the meantime, if you have any ideas or information, please let me know.

John Wingham

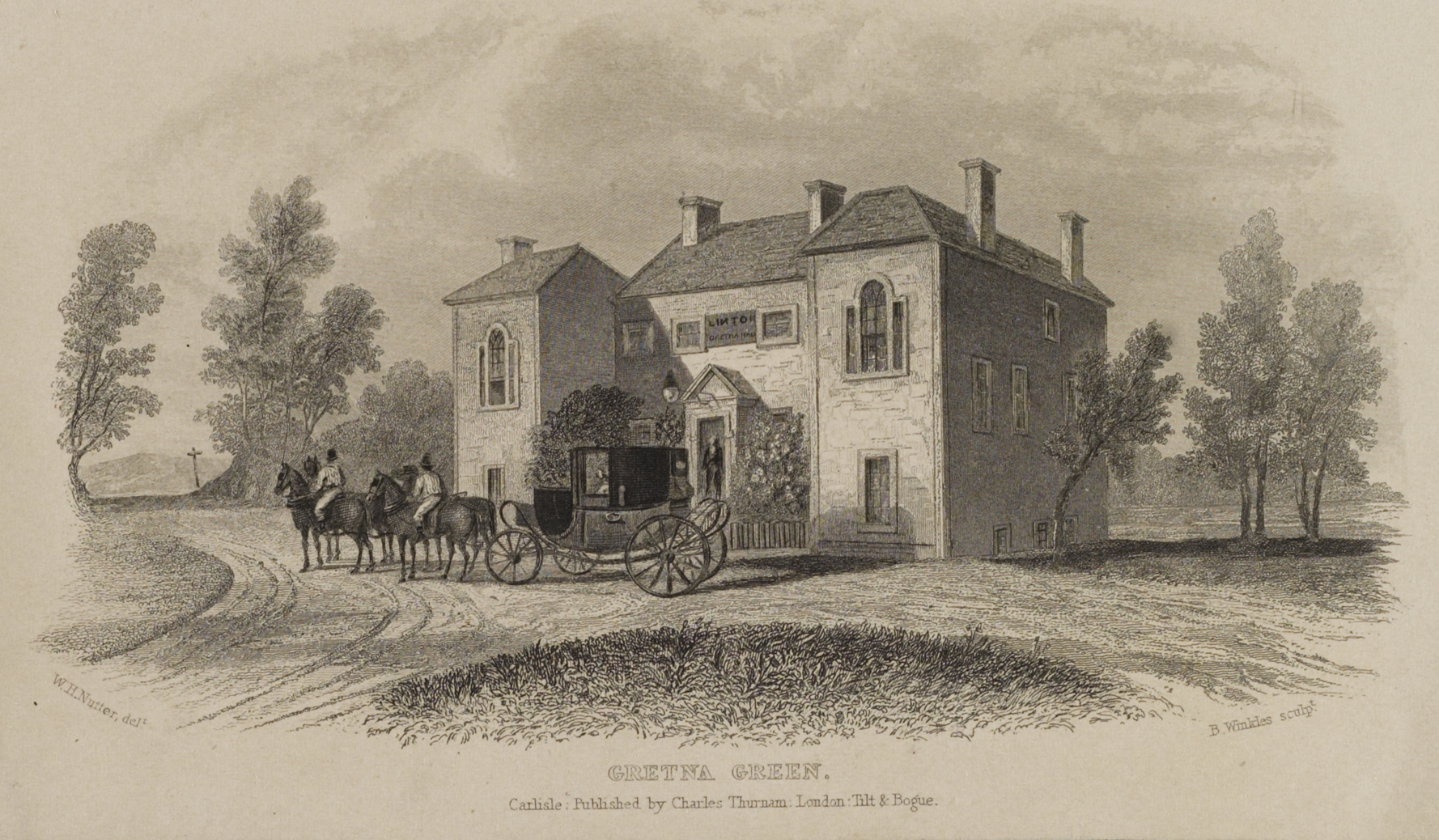

Marriage in the 18th century

Marriage regulation in the first half of the eighteenth century was almost non-existent. You were supposed to get married in your parish, but this was often expensive and slow. If you had moved a long way away, then it was impractical and no good if the woman was pregnant and a quick wedding was required. If you lived in London there were the Fleet Marriages, and the notorious Reverend Keith who performed hundreds of weddings at his chapel in Westminster. They were cheap and quick and mainly honest and if all else failed there was Gretna Green. It enabled couples to marry outside of their class and avoid arranged marriages and the dynastic or commercial interests of their parents.

There was however a sinister side. A young wealthy heiress could be kidnapped and raped. Her reputation on the marriage market ruined she had no choice but to marry thus enabling her “husband” access to her fortune. Everything a women owned became the legal property of her husband once she married.

The state defined these weddings as either irregular or clandestine marriages and there had been a number of scandals. It also undermined the position of the Church of England. The main driver was not, however religion but the transfer of power and money between aristocratic and wealthy middle-class families who didn’t want fortune hunters or love interfering with their arrangements. In 1753 parliament decided to do something about it. The result was Lord Hardwicke’s Marriage act.

The act required that for a couple to be married legally they must be over 21 or have their parents or guardians’ permission. They either must obtain a special license from a bishop or have banns read for three consecutive weeks in their parish church and they must be married by an Anglican priest in a church between the hours of 8 and 12pm. The only exemptions were for Jewish and Quaker marriage ceremonies.

There were loopholes. The law did not apply in Scotland so there was still the option of running away to Greta green or you were wealthy enough or a bishop was your uncle then you could get a special license to marry your heart’s desire.

John Wingham

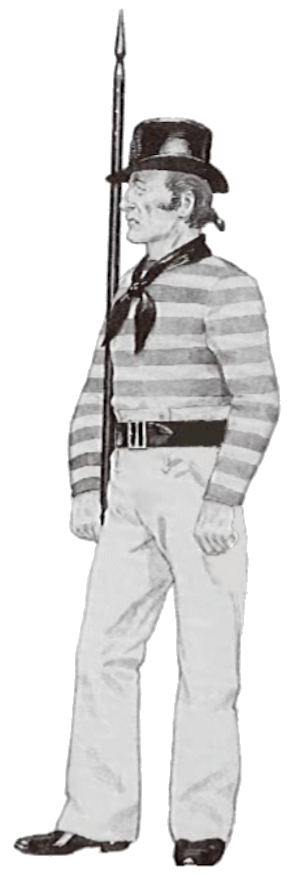

Sea Fencibles – Brighton at War

Brighton had often been attacked by the French, but these were hit and run raids. Revolutionary France in the 1790’s ,however, was a much more dangerous threat. Brighton was by then a wealthy target and a one of many possible landing areas for a French invasion fleet. In 1794 the Government constructed two-gun batteries in Brighton and from Yorkshire to Devon began building coastal defences. However, more needed to be done to protect the coast and channel trade.

In the small inlets along the French coast as well as the seine estuary and Cherbourg lurked French privateers. Ranging size from small fishing boats packed with boarders to 24-gun sloops, they posed a threat to Brighton’s fishing fleet and ships sailing down the channel. The answer was the Fencibles a slang shortening of defencibles

It was the brainchild of the royal navy captain Sir Home Popham. When in charge of defending a port in Belgium, he had conscripted and armed the towns fisherman to see off the French navy. He put this idea to the admiralty and in 1798 the sea fencibles were born. It was they who would man the shore batteries and newly constructed Martello towers.

The fencibles were paid and were exempt from the navy press gangs and were not required to serve abroad. Some 30000 were recruited across the country. An extract from an advert in a Suffolk newspaper in 1798 gives a flavour of what a recruit could expect

“They are only required to attend one day in the week, to exercise at the pike and guns a few hours, and will be allowed a shilling each on those days, and if called up on actual service, the pay of an able seaman, and Eight-pence a day subsistence.“

There were also career and financial opportunities. Fencibles could receive prize money from ships they captured and could become petty officers on 2s6d a day. Lieutenants and Captains received a lot more.

36 separate commands were setup covering the coast from Yorkshire to Cornwall. This area’s headquarters was at Shoreham. The sea fencibles were however not a just defensive force. Trained and equipped with uniforms and arms and with up to 4 small canons mounted on their fishing boats Brighton’s fencibles were to seek out French privateers and capture or sink them. But not everyone was happy, the treasury complained that the fencibles could include smugglers who could use their service as a cover. Objections were even made when fencibles rescued sailors from wrecked ships.

The fencibles took many French ships and prevented others being taken. Their last action was on February 3rd 1810 off Newhaven. A French privateer had taken a brig. (a small two masted ship) .Though outgunned five fishing boats set sail to recapture it. Although they failed, they were able to save another boat and drive the French off. However, it was clear by now that there was no invasion threat and the fencibles were disbanded later that month.

As fishermen and sea men many of Martha’s relatives and even her close family would have served in the fencibles. It paid well when fishing was impossible due to the French or the sea and of course it was about being able to defend your home and livelihood.

John Wingham

Mothering Sunday or it’s not about Mothers

Its easy because of the title to think that Mothering Sunday is about mothers, sadly it wasn’t. The Mothering Sunday of the 18th century was a very different day. It was originally a medieval holiday held on the Sunday of the fourth week of Lent. It was expected that you would return to your church of origin, your mother church, where you were baptised. There were processions and a sort of celebration of mother hood as services were around the Virgin Mary. It was also a chance for people have a time out from Lent, to eat, visit relatives, and enjoy themselves.

After the reformation in the 16th century. It started to change and by Martha’s time you didn’t have to visit your home church just go to your local parish church or nearest cathedral and of course, this being the 18th century, a feast and a party. There were even special buns made for the day. It was also a holiday for household servants as they were allowed to go home to spend time with their families.

In the following century as Lent became less important and celebrated it seems to have gradually been forgotten. It was in the early part of the 20th century that it was revived, not to celebrate the church but mothers and motherhood. It still remains a religions celebration but has also become a secular and commercial event.

John Wingham

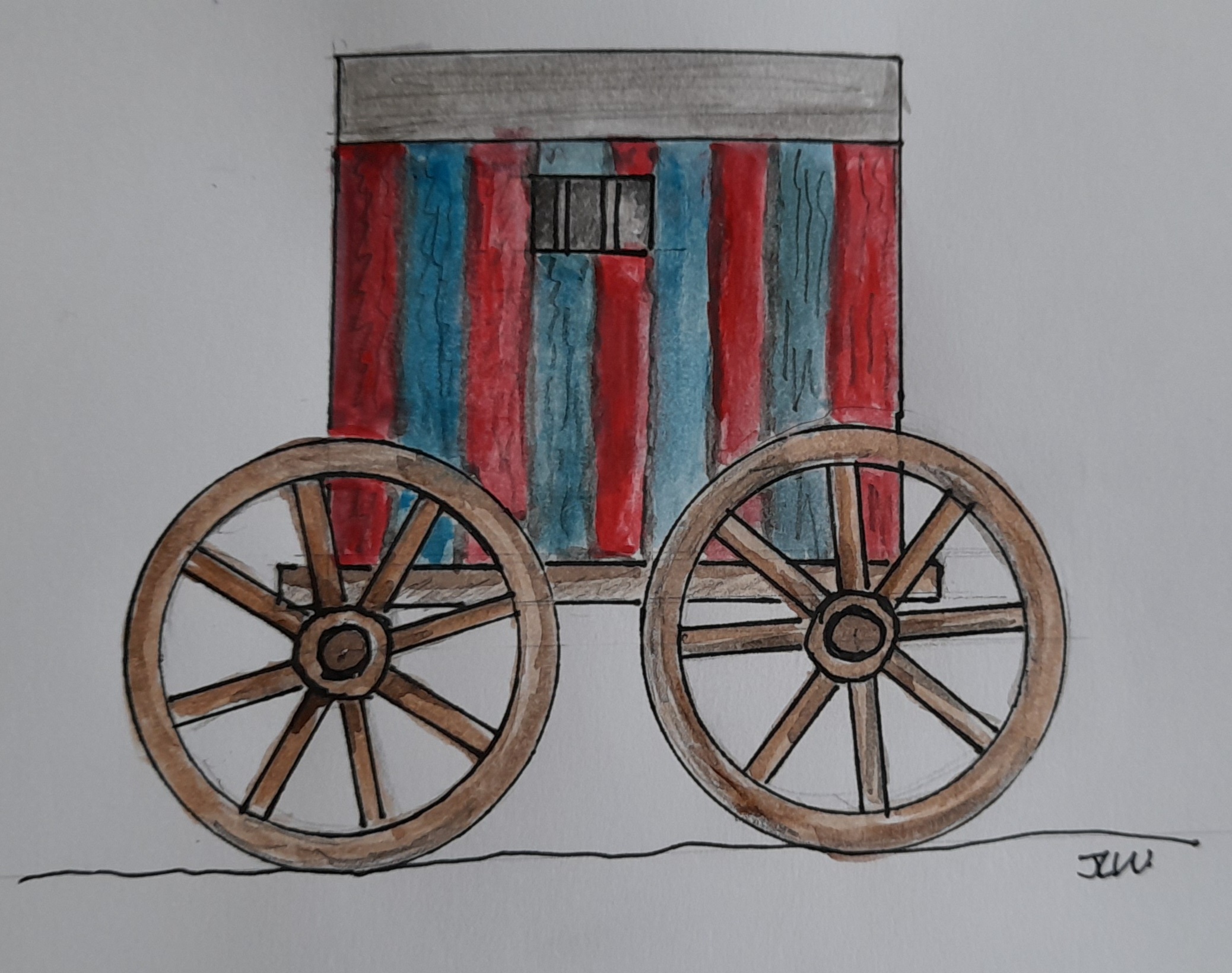

The Bathing Machine

Invented around 1735 the bathing machine would have a profound effect on the coastal towns of Britain. It would catapult Brighton into one of Georgian ‘must go to ‘ towns that would rival Bath. It also made our Brighton into one of the UK’s premier tourist destinations.

There were many variations on the design and each area had its own design. There are no pictures from the mid-18th century but cartoon and drawings from the 1800’s and photographs from later in the 19th century show what it looked like.

The Brighton bathing machine was a simple box approximately 2m long, 1.8m wide and 2.3m high including the pitched roof. It was painted originally in primary colours often in stripes but the colour would soon have faded. It had a door at either end and a small side window high up to provide ventilation. It was mounted on a chassis with large wheels at each corner. These were around 1.5m in diameter and had a wide iron tyre with studs to give it greater grip on the beach.

There was movable step to allow access and inside a bench and coat hooks. The machine was either towed into the sea using a pony or would be dragged in by the dippers. We can get an idea of what they looked like. There is one in Margate operating as a sauna but if you don’t want to make the trip just stroll along the front and look at the brightly coloured beach huts. When the bathing machine fell out of favour around 1900 the wheels were removed, and they were repurposed as beach huts.

John Wingham

A Tale of the Bath - Sea Bathing circa 1790

We can only guess at what it was like to be dipped. So here is a short story that tries to imagine what it would be like.

Today was the day, she was to be dipped. Amelia was 15 but was had been very ill. Her family’s doctor had recommended that sea bathing would help her get better. Wrapped in her fur lined cloak with her maid Alice behind her she stepped into the street.

Father was waiting by the carriage and helped her in. With a lurch they set off. From the coach’s window Amelia could glimpse the sea glittering in the bright November sunshine. Father pointed towards a small and rather fat old lady in a heavy dark blue dress with a grey shawl walking towards the sea… He said , “that is Martha Gunn the most famous of the dippers and a friend of the king”. Amelia waved as they passed, and the old lady raised her stick and smiled. “Is she going to dip me then?” “ No” said father” it will be her relative Lizzie Wingham. All the family is involved!”

As the coach reached the shore Amelia could see strange little huts on large wheels. Some had a pony harnessed to it and there were a number of working women in black bonnets and shawls, some were around the huts, others huddled around braziers trying to get dry. “See Amelia” said father “those are the bathing machines and the people around them are the dippers” Amelia was both excited and nervous as she had never been in the sea before.

They stopped on the promenade and father helped her down from the carriage and they made their way over the pebbles towards a blue and white stripped bathing machine with a small wet pony harnessed to it. They were greeted by a healthy-looking middle-aged woman. Her hair and clothes were sopping wet, and water was dripping off her greying hair. Standing next to her was a tall girl equally sodden. “Welcome sir! Is this the mistress to be dipped? This is Miss Marshall replied father”. “Pleased to meet you Mistress would you go into the machine your maid can help you undress and prepare”. Lizzie then told her assistant Charity to move the pony and attach him to the front of the machine.

Amelia followed by Alice climbed up into the machine. It smelt of sea and damp. Amelia undressed removing even her chemise. Alice held out an undyed linen shift. “What’s that, I’m not wearing that”.” I’m afraid you will have to,” said Alice. “It’s for the bathing its stops men seeing your legs and other parts.: “If I must then”. Alice helped Amelia struggle into the scratchy garment. It was heavy and damp. “Why is it so heavy” Amelia asked. “Well, “, said Alice” it has weights sewn around the hem to stop the waves pushing your dress up”.

They could hear the pony being attached to the front of the machine. Then they were off crunching across the pebbled beach and into the sea. The waves sloshed against the sides and water started spurting through the gaps in the floor. The machine lurched and stopped.

Amelia opened the door. The sea came almost to the threshold and looked so cold and grey. Mistress Wingham, up to her chest in the sea, offered her hand to help her down. “Come on dearie don’t be scared you’ll be laughing with your friends as soon as its over”.

Amelia shuffled forward onto the first step and into the water. It was so cold. She stopped but then at Mrs Wingham’s urging took another step down then stopped again frozen with fear and cold .”I can’t swim !” Like lightening Lizzie gathered Amelia up in her strong arms and dunked her into the water. As Amelia surfaced Lizzie held onto her “I think that will do for your first time” and she helped Amelia up the steps into the bathing machine. She was wet and hair was a tangled mess. Alice looked at her and tried not to giggle “Come on then let’s get you out of that and dry and dressed”. As she dried the machine started to move back up the beach.

Now warm in her fur lined cloak Amelia stepped out of the machine, she felt alive and bright. Lizzie stepped forward and handed her a glass of hot shrub. Mistress Wingham, I feel so good, thank you”. “So ,you will be back?” asked Lizzie. “Yes, I will as long as you don’t throw me in.” As Lizzie laughed as she turned away toward a brazier, “it was only a little push”

John Wingham

The Last and Fish Cart (The Cricketers) by A. F. Griffith.

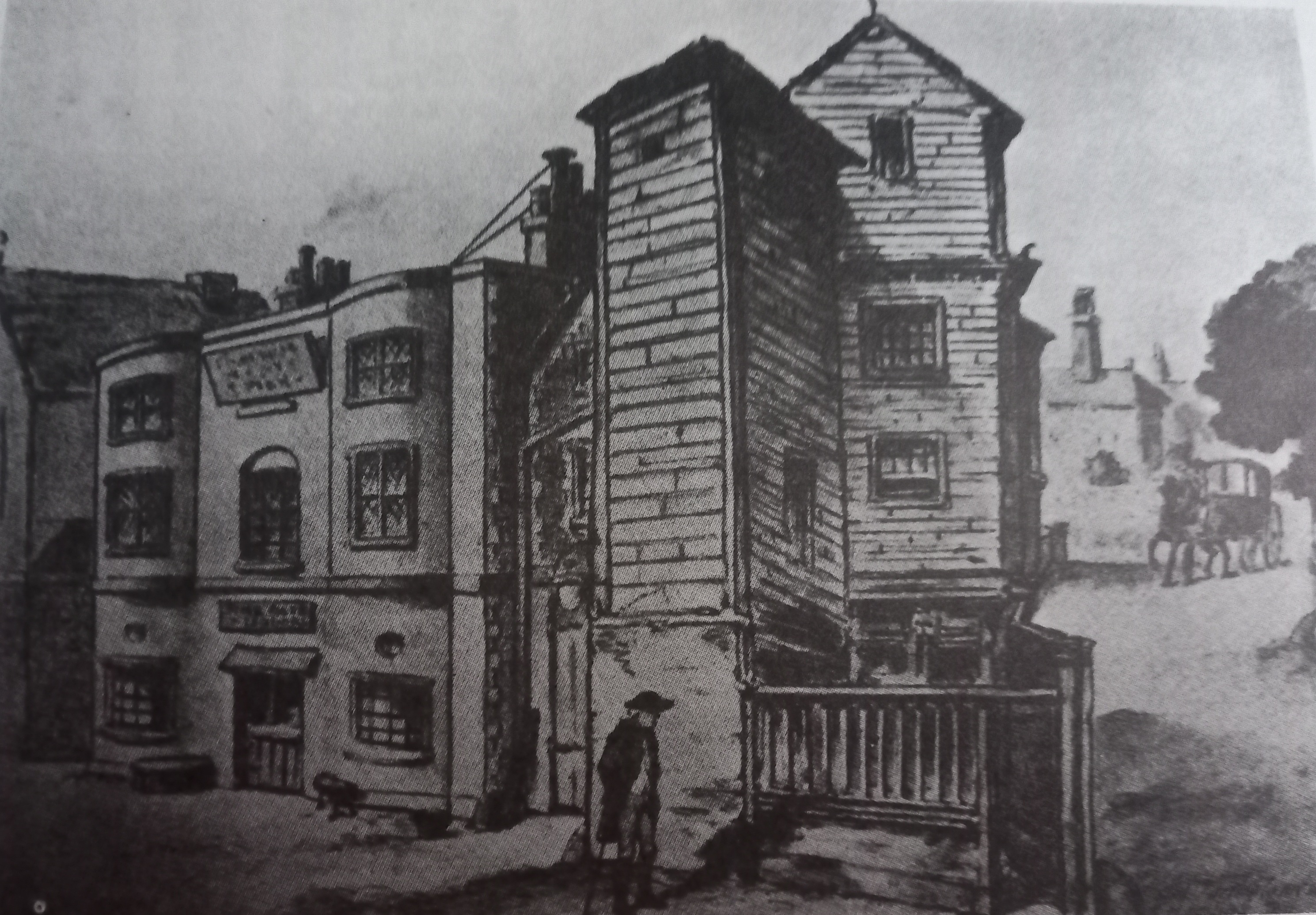

A Pint of Beer and a Drop of Brandy - The inns and pubs of 18th century Brighton

Martha and her contemporaries would not have recognized the name Brighton. To them it was Brighthelmstone. It was originally bounded by North Street, East Street, West Street. Middle Street was added later. There was a South Street but this was swept away by the 1703 and 1705 storms. In between the main streets were narrow alleys or twittens, what we now know as the Lanes. This was the heart of Brighton and would remain so even as the town expanded.

The earliest pubs that we know of go back to the 16th century. They weren’t called pubs then, either ale or beer houses or inns. Ale houses were run by ale wives. They were often widows who had been given a licence by the parish to open an ale house to support themselves. They brewed their own beer and served it in their front room. 16th century Brighton would have had many of these scattered through the Lanes.

The first Inn that we know of was the Laste and Fishcart founded in 1545, now the Cricketers. The Old Ship, now a hotel, was first documented in 1665. These served a ”better class” than the alehouses and had rooms for travellers.

As in many other areas the 18th century was for Brighton a period of upheaval and opportunity. As the towns tourist industry developed, old buildings were converted or expanded or new coaching inns were built. These were more like hotels. There were several along North Street as this was the main road into the town from London. The White Lion, on North Street, originally a 16th century building stood where the Bootsstore is today and was operating as a coaching Inn by 1790 or earlier.

The only surviving building was once the Clarence Hotel but was opened as the New Inn in 1785. It was very large, and its stables could accommodate 80 horses. The Castle Inn, which stood in what is now Castle Square, began life, as many establishments did, as a house but went upmarket in the1757 and added the first assembly rooms to cater for the emerging social scene.

As many inns went up market, and brewing became more commercial, the alewives were replaced by what we would recognize as a pub. They were larger serving a wider clientele. They would serve food and many would have brewed their own beer. We know of several in the Lanes, The Spread Eagle now the Sussex Arms [ Martha’s cottage 34 East St is now part of it] had been going strong for many years, the Black Lion and Spotted Dog were both open by 1791 and more would open to meet the growing demand.

Yet the idea of the small local ale house somehow survived in Brighton. If you walk around the city today away from the tourist areas, you will come across little pubs occupying terraced cottages, offering good beer, food and, on some nights, music.

John Wingham

The dark side of the Martha’s life.

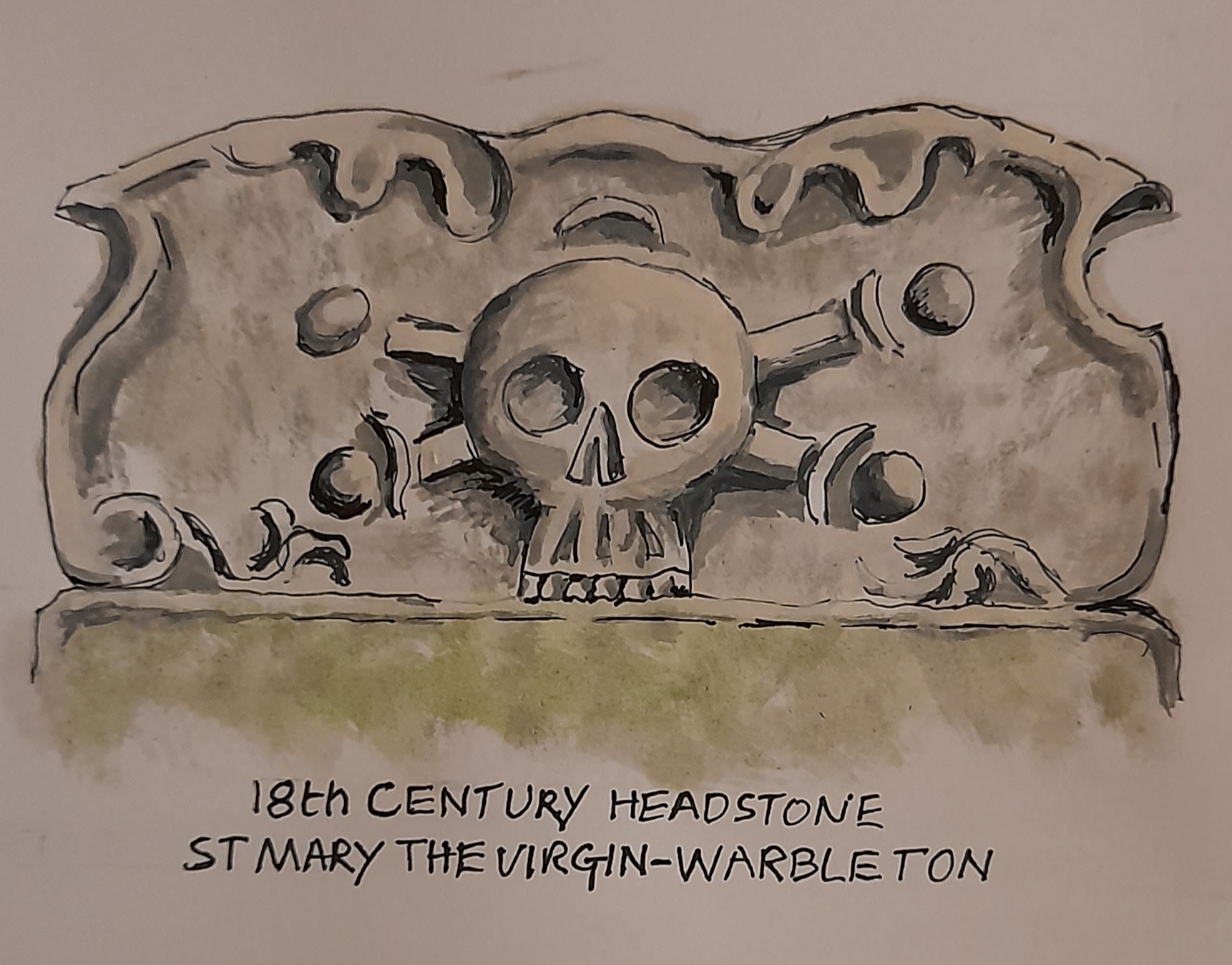

We tend to look at the 18th century through the eyes of Emma or Mr Darcy. But it wasn’t like that even for the wealthy. For most it was a hard struggle and worse in the cold of winter. Life could be short and child mortality, even for the rich, was high. Often when a woman married her shroud would form part of her trousseau as she had a high chance of dying in childbirth. Martha, over her long life had 8 children of whom four died, and many grandchildren but we don’t know if she had any miscarriages. Her husband Stephen died before her, and she had to attend many funerals not only of some of her children but her relatives and friends.

Georgian funerals and mourning were nothing like the Victorian death cult that would develop in the following century. There were big state funerals although mourning the monarch was not done. There was also a loose etiquette which was followed in so far as your social class determined or you could afford it. There was a wake and food played a big part in the proceedings. There were special biscuits to be eaten at the wake, and neighbours would contribute food. Swift observed that morning was neither sombre nor strict and was a celebration of a life. It could also be the butt of jokes. The Town and Country magazine [Vol. 1 1769] satirised the mourning periods that were supposedly expected.

“Wives’ mourning their husbands were expected to mourn for 4 months. However, on the third month “she was allowed for laughter at a play or dancing with her prospective bridegroom”. On the fourth month she was permitted to “to jump into her intended arms and end her widowhood.” As usual men got the better deal, he only had “to mourn for two months at the end of which he could obtain more mistresses if he chose not to marry”.

For Martha ,a mother and grandmother, it wasn’t like that. She would have worn black, maybe just a black scarf but in spite of the tears and sadness she had to continue to work and look after her family. Eighteenth century mourning was a personal thing and a family affair, and they would mourn how and for whom they wished

But death could override the class system. In 1750 the English author, Charlotte Lennox, in the biography of Harriot Stuart, wrote that “[The] length of time devoted to mourning, and the apparent intensity with which one mourned, were determined to a large extent by the relationship that … existed between the two people and the ‘public knowledge of that relationship’. When it came to death the social conventions were set aside. You could mourn for one of your servants and in doing so you were saying to the world that he had been your friend.”

John Wingham

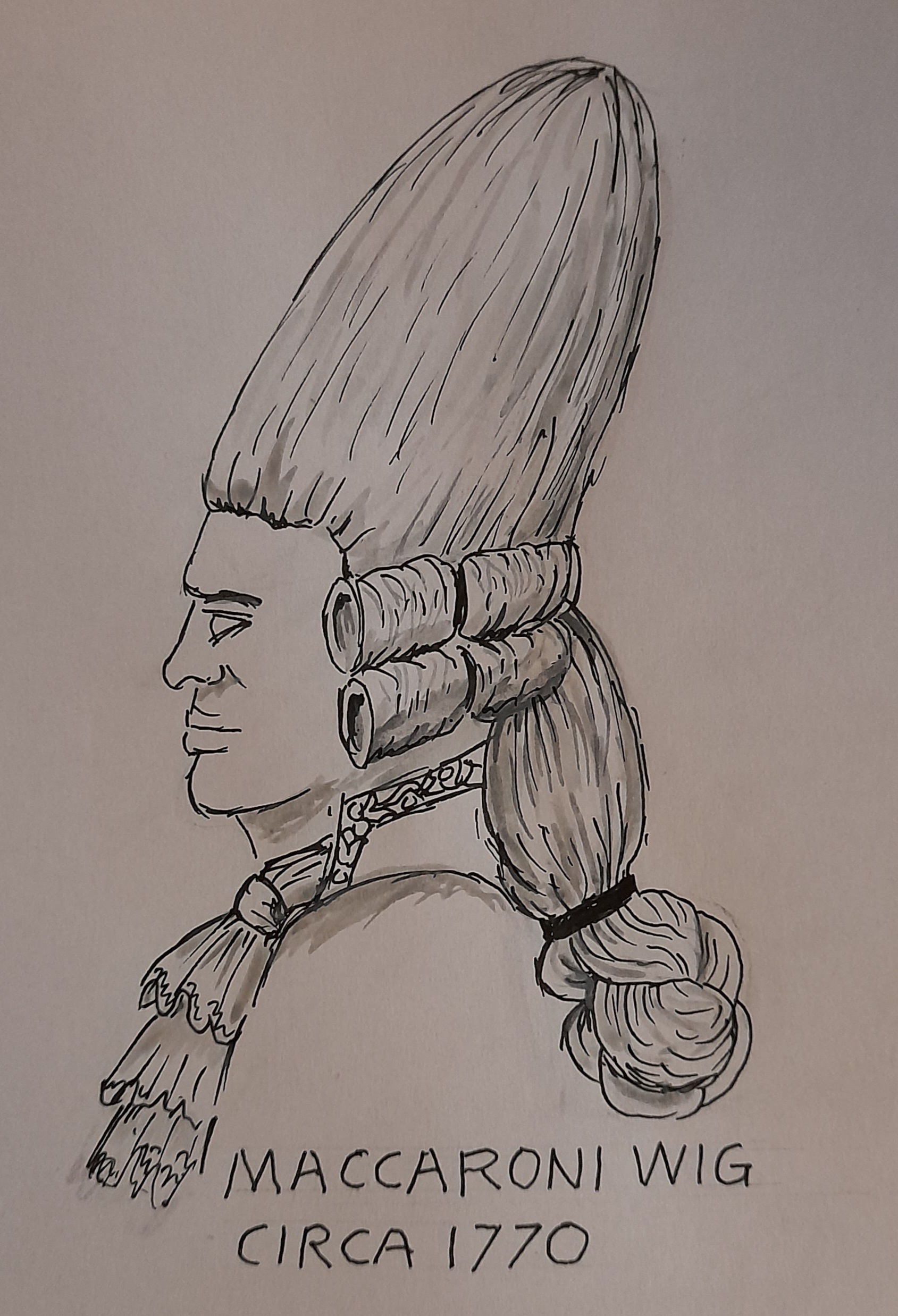

Macaroni or Maccaronis ?

Martha lived through the fashions of the 18th century and as Brighton became more fashionable, she would have seen them come and go. One of the strangest was the Maccaroni and I am not just only referring to pasta.

Originally it was a fashion for the wealthy young nobles who went on the grand tour. They always took in Italy where they developed a taste for macaroni. This type of pasta was unknown in Britain at the time so to it became a code for those who had been on the tour.

In 1764 they founded the Maccaroni club. Many wealthy bourgeois young men, who hadn’t been on the tour, adopted the style, and it rapidly developed into a subculture with its own fashion and language. They were known for heavy gambling and drinking and generally making a nuisance as well as undermining the class system. As the century progressed Tobias Smollett commented in his popular novel, Humphry Clinker, that ‘The gayest places of public entertainment are filled with fashionable figures, which, upon enquiry, will be found to be journeymen tailors, serving men and abigails [ladies maids], disguised like their betters. In short, there is no distinction or subordination left’.

The Maccaroni look was androgynous, effeminate and outrageous and if the cartoons of the period are right there was a lot of cross dressing. The Macaroni fashionista wore a highly decorated waistcoat over which went a tight-fitting jacket. This came down to the mid-thigh so was shorter than the usual coat. The breeches and stockings were brightly coloured. The shoes, usually red with high heels, had large metal buckles and bows. The cravat or jabot was large, flouncy and lace edged. A large bunch of flowers was worn on the left shoulder.

Men of the period usually wore wigs whereas fashionable women of the 1760s, and 70’s dressed their hair using tall frames. These elaborate styles were then decorated with jewels, feathers, and real and artificial flowers. The Maccaronis were not to be out done and wore tall and elaborately shaped wigs often topped off with a small tricorne hat. They were so high it was said that the hat could only be tipped off with a sword. There was even a song, Yankee Doddle Dandy the lyrics of which include the line “put a feather in his hat and call him Maccaroni”.

With their over-the-top dress and effeminate style, they were an obvious target for the cartoonists and satirists of the day. Yet it was in many ways it was very modern thing, just think of goths, punks or mods. Maybe it was the first youth culture? What Martha made of it all we don’t know but being the practical women that she was she probably had a good laugh.

John Wingham

When is a shrub not a shrub?

At Christmas we often buy a poinsettia, but Martha’s shrub was a drink not a plant. It was an early cocktail or mixer and was usually homemade. The base was either rum or brandy and occasionally gin. It was made by boiling sugar with lemon or orange zest. It was an open-ended recipe; it could be and was made with any fruit that was available. Spices such as cinnamon or mace could also be added. It was a sweet and sour drink so if a citrus fruit wasn’t available then cider or wine vinegar was substituted.

It would have been around 30% alcohol with a refreshing sweet and sour flavour. Most contemporary cookbooks have recipes for it. There is even one for brandy and rhubarb. It was a popular and versatile drink and could be drunk neat as a refreshing cordial or mixed with wine or cider. It was also used as the base for the less alcoholic punch. It’s still around today. Think of Baileys or the flavoured gins that are on sale in most supermarkets they are just our modern version of Shrub.

Martha’s cookbook has recipe for it which uses brandy and lemons and milk. I have adapted it. So if you want to have shrub for Christmas now is the time to make it

You will need:

500cl of Brandy, rum, or gin

200cl water

50cl of cream or milk

50g sugar, if you decide to use rum then you could use a light brown sugar

Zest of three lemons or 2 large oranges or you could mix them.

Method

Put the sugar, zest and water and bring to the boil. Then turn down the heat and simmer for a further 5 minutes. Heat the milk and allow to cool a little then add the milk to the sugar water. Do not strain.

Remove half of the alcohol of your choice from the bottle. Pour the sugar and milk mixture into the bottle and top up with the reserved alcohol and reseal the bottle. Drink any alcohol that you couldn’t get back in the bottle.

Then the hard bit, leave it for three weeks then strain the shrub through a coffee filter or muslin. Put back in the bottle and top it up. It’s now ready to drink.

John Wingham.

Did we forget the Twelfth cake?

Twelfth cake like the plum pudding had a long history. It probably started off as a sweet bread stuffed with raisins. The invention of the cake hoop and the use of egg whites as a raising agent in the 17th century turned into the type of fruit cake we would recognise today. You won’t find a specific recipe for it in any cookbook it was so common that everyone knew how to make it. It was always served at a final feast on the 5th January the day before epiphany, and marked the end of Christmas. The sixth of January was the start of the agricultural year but January and February was a hard time for many.

Like the Christmas pudding it was the centre of the feast. It was a fruit cake made with butter and eggs, spices, and dried fruit. The Scots made theirs with whiskey the English with brandy. In the early Georgian period, it was probably just lightly iced or not at all.

By the 1790’s, when Martha was having her portrait painted, it had become far more elaborate. It was now covered in marzipan and iced, the icing was usually red but could also be green. It may have been decorated with sugar figures and it could be huge 20 lbs or 9 kilos seem to have been common. Yet inside it the cake carried a remnant of its past. Before it was baked a bean, and pea or silver coin would be placed inside. Whoever got them became the king and queen of misrule for the day. Did Martha ever win the pea, did she watch her grandchildren become the lords of misrule?

We will never know for we have forgotten twelfth night but not the cake. It survived through the most of 19th century but as twelfth night faded away it lived on as our Christmas cake. So when you cut your Christmas cake go a little mad and let your inner lord of misrule out!

John Wingham.

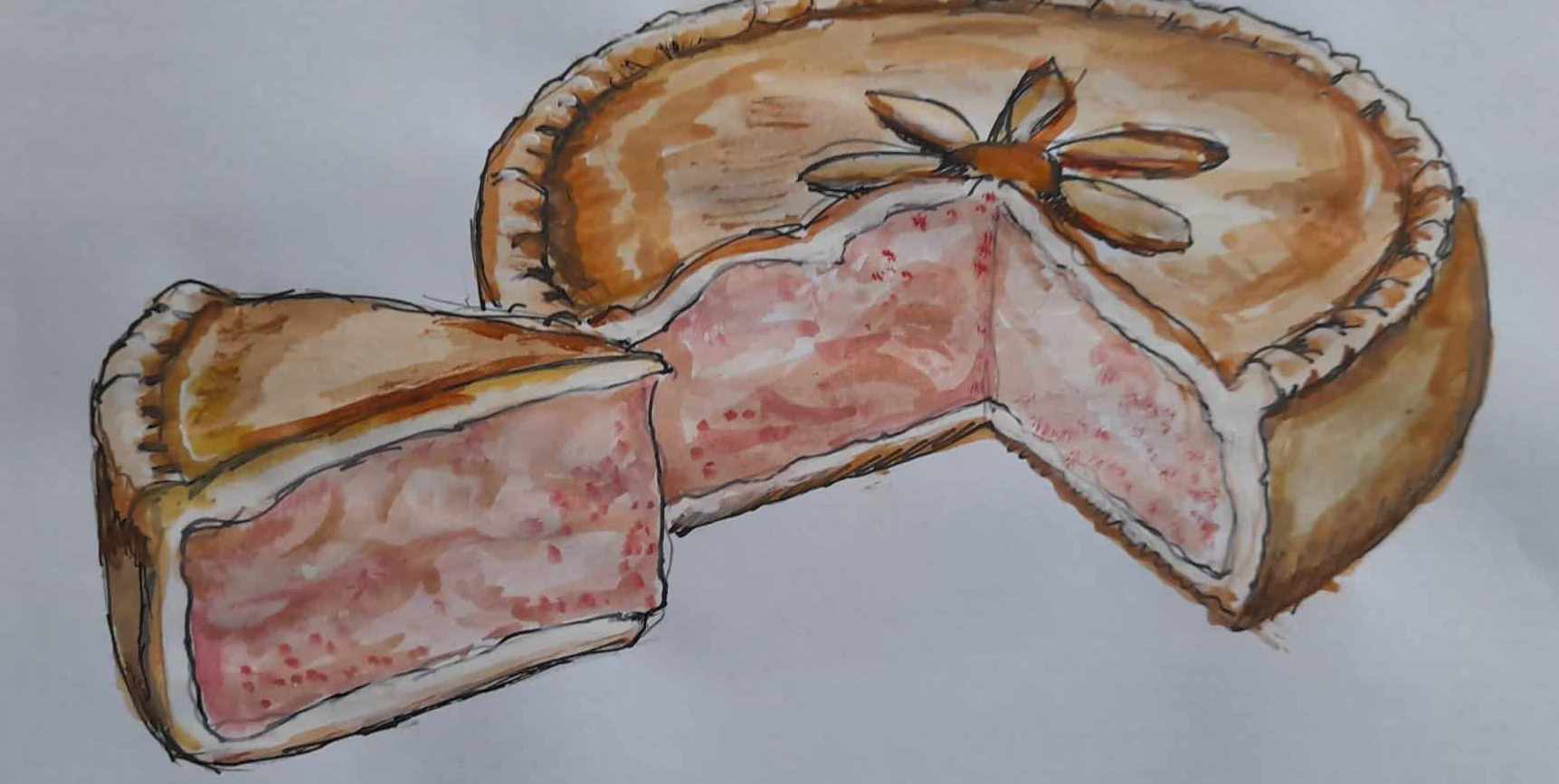

Another slice of Pie

I like a nice large pork pie. On boxing day with some pickles and a glass of beer it doesn’t get any better. But our ancestors went several steps further. They revered the pie and none was more magnificent than the Christmas pie.

They had always been pies, some were hardly edible and were just for show. The duke of burgundy did have four and twenty blackbirds, not exactly baked, but were actually in a pie. Our ancestors dispensed with the medieval performance pie and went for something you could eat. The result was the Christmas pie!

The pie was a type of game pie and used a raised pastry just like our modern pork pies. It was usually large, and there are many recipes for it. The largest versions use 15 to 20 kilos of flour, and a whole turkey just for a start. Then pork, spices, other game birds, almost everything that could fly went in. Finally the pie would have had pastry decoration and been egg washed to give it a golden sheen. It would have taken many hours to cook and the pastry of a pie of that size may not have been edible. I would guess that most were a lot smaller. Did Martha have one on her Christmas table? I for one think she did, after all who can resist a good pie.

John Wingham

How the plum pudding came to Christmas!

During Martha’s lifetime there was no Christmas pudding as such, in fact the earliest reference to a Christmas pudding is around 1845 though American cookbooks were using the term much earlier. Yet at Christmas in England there always a plum pudding. It was indispensable part of the traditional feast whether you were rich or poor. It would be served in the poor house, on warships and at the king’s table.

It was certainly being made during the Tudor period. There are many recipes for it written by both aristocrats and by professional cooks like Hannah Glasse. It was always supposed to have 12 ingredients for the apostles and one for Christ yet was simple pudding to make. Fat usually suet, flour, left over breadcrumbs and sugar was the base to which was added spices like cinnamon and nutmeg and dried fruit. This was mixed together and put into a cloth which was tied at the top and boiled in a cauldron over an open fire for many hours. The pudding was round like a cannon ball and could be served with a brandy and butter sauce or a Madeira sauce.

It was a peculiar British pudding and the precursor of the steamed puddings of the Victorian era that we still eat today. Without it there would be no sticky toffee pudding.

Just one further fact there are no plums in a plum pudding. The plums were in fact a type of large raisin that our ancestors called plums!

John Wingham.

St Nicholas Church by William Alfred Delamotte

Image from Brighton & Hove Museums Collection.

Christmas Day with Martha

The 18th century Christmas bridges the late medieval and Tudor celebrations and how we do it today. So how would Martha and her large family and her even larger extended one have celebrated Christmas? Martha and Stephen Gunn were not poor just comfortably off so they could afford to celebrate in style.

Christmas was the biggest celebration in the 18th century calendar. It started on the sixth of December with parties and balls but for the agricultural worker it was a lean time as work had stopped and they weren’t paid. For the bakers and others it was a time to make money.

It really kicked off on Christmas Eve. This was the start of the 12 days of Christmas. Houses would be decked out in anything green; holly, ivy and mistletoe were the favourites. Kissing balls were made of green stuff and mistletoe and were hung from the ceiling. The Christmas tree had been introduced by Queen Charlotte but hadn’t caught on. On Christmas eve families still brought in the Yule log, [a real log not made from chocolate], into the home to burn. But everything centred around eating and drinking and the Christmas Day feast.

Christmas Day started with a trip to church then back to the house for the feast. The food was laid out in two or three removes. These were not courses as we would understand them as each remove consisted of several dishes both sweet and savoury and the diners helped themselves. I would imagine that Martha’s family would just have set the table with everything and then added more as they ate. So what were they sitting down to, what was on the table?

The centre piece was the meat. For the elite it would be venison, for the poorer familes goose. Turkey was available but the preferred choice was beef. This was spit roasted over an open fire. Underneath it was a drip tray for the fat, and this was used to make a batter pudding, probably the origin of our Yorkshire pudding. The meat would be served with the seasonal vegetables like cabbage, parsnips and carrots. There would be no potatoes as people hadn’t got used to eating them. There would have been lots of bread and butter as well as soup, frumenty (a type of savoury or sweet porridge} and pease pudding. There would, if the seas were kind, be fresh fish baked in butter sauce

Then there were pies. The Christmas pie was large and filled with different meats. It was probably brought in but the smaller mince pies, which were still made with meat as well as fruit, could have been home-made.

There would have been various other sweet dishes but there was always the twelve cake, the ancestor of our Christmas cake and of course the plum pudding. We will look at these dishes in more detail in future mini articles on Martha’s Christmas. And for the Gunns it would be washed down with cider, beer and if you had smugglers in the family maybe some wine and brandy.

John Wingham.

The Hurricane that Made Brighton

The great storm of 1703 was one of the worst to hit Britain. Today we would class it as a category 2 hurricane. It struck on the night of 26th November though this is the old Julian calendar date. On our calendar it was the 7th December. Whatever the date over 8000 people died. Hundreds of ships were lost and towns wrecked. The wind was so strong that the 95-gun battleship HMS Association was driven back across the North Sea to Sweden.

Brighton was, before the storm, the largest town in Sussex with a population of 6000. Its major industry was fishing but it was facing competition from the new harbour at Shoreham. The great storm wrecked the town. It stripped the rooves from buildings, destroyed at least two thirds of the fishing fleet and around a hundred houses were washed into the sea. The famous writer Daniel Defoe described the town as “looking as though it had been bombarded”.

Worse was to come. The storm of 1705 wrecked what was left of the lower town and buried much of it in shingle. By 1720 John Warburton described the town as “a large, ill-built, irregular market town, mostly inhabited by sea-faring men, who choose their residence here, as being situated on the main (sea), and convenient for their going on shore, on their passing and re-passing in the coasting trade”, the “sea having washed away the half of it; whole streets being now deserted, and the beach almost covered with walls of houses being almost entire”. The population had fallen to 2000 and to Warburton’s regret only one ‘gentleman’ lived in the town.

But it wasn’t the gentlemen who would turn Brighton’s fortune around. It was the tough fishing families of Brighton, The Killicks, Winghams, Collins and Gunns as well as many more. It was Martha’s parents’ generation that secured the towns future. They built new boats and when later, in the 1740’s, the new-fangled health craze of sea bathing took off, they were there building bathing machines. It was Martha and her generation that developed the company of bathers and turned Brighton into a destination to rival Bath.

John Wingham

The Old Ship Assembly Rooms by William Thomas Quartermain. c.1800. Image from Brighton & Hove Museums Collection.

A Place to Meet in Martha’s Brighton

Our Brighton has pubs, theatres and nightclubs and many other places of entertainment … but how did it all start and how did our Georgian forebears enjoy themselves? The answer was the Assembly Room.

Part nightclub, dance hall and casino no town could be without one. Assembly rooms were a key element in the Georgian social scene. They varied in size and in small towns they might just be a large room. In places like Bath or regency Brighton they were much more complex. There would be a ballroom with several smaller rooms off it. These would be used for suppers, gambling, afternoon tea, or recitals. When a ball was being held, then one room would be the retiring room where the ladies could rest or fix their makeup. During the day they would act as a meeting place for tea and conversation.

Assembly rooms were one of the few public places were both sexes could meet and where marriages were often arranged. They were for the well off, and the elite of society. They were not open to all. For some halls attendees were screened and unmarried women were always chaperoned. Admission could be by invitation, subscription or, in the more down-market ones, just by buying a ticket.

The earliest assembly room in Brighton was in the, now demolished, Castle Inn in Castle Square. In 1752 a large hall was built behind the Inn. In 1766 as Brighton was becoming very popular it was expanded and upgraded. The Old Ship Hotel on the sea front followed in 1767.

The Assembly rooms at the Old Ship hotel were typical. They were constructed at the side and rear of the building. It had a ball room on the first floor which was large enough to host the Prince Regent’s ball. The ball room also had several smaller rooms for other entertainments. It also provided other services. Until 1777 Brighton’s post office was located there. As Brighton became more popular more assembly rooms were opened and by 1820 there were at least 6.

Even though Martha was popular and known to the aristocracy she was working class and unlikely to have gained entry!

John Wingham

Pies – the Georgians must have food.

All countries have many kinds of pies but the British and the Anglo speaking world surpass them all. Everywhere the British went so did the pie. No Georgian banquet would be without the centre piece of a decorated game pie and no Cornish tin miner would be without his pasty. So what was so special about the British pie? Where did it come from?

We need to go back 300 years. This was a period when all cooking was done on an open fire or on a charcoal grill. The only oven was used to make bread though tarts would be made in them as well. To cook more delicate items the cook used a large iron casserole with a dished lid. This allowed coals to be heaped onto the lid. This gave a more even heat, but the contents would still be likely to burn or dry out. To avoid this a cold-water pastry would be used to wrap the meat or mixture in. Known as a coffin it would be discarded and the cooked contents served up on a platter. But this was only for the well off.

It wasn’t until the late 17th century that the pie really took off. Pies were already sold by street sellers but now bakers were opening shops and with the new cast iron ranges and profusion of fruit and meat the pie came into its own. Cherry, apple, plum, mince, asparagus, venison and game pies, the Cornish pasty, the scotch pie. and of course, the pork pie. Many parts of the uk have their own pies, London has pie and mash, Cornwall the stargazzy pie but there are many, many, more. The Americans surpassed even the British in the different types of pies they made. Individual states had a state pie, and the national dish of Australia is the meat pie. So, whenever you are passing a bakers take a look at the not so humble pie.

Did Martha eat pies? She is depicted as a large lady so maybe she did !

John Wingham